INTRODUCTION AND BRIEF DESCRIPTION

Believing the complainant consented to sexual activity is not a defence if it resulted from self-induced intoxication or failure to take reasonable steps to ascertain consent.

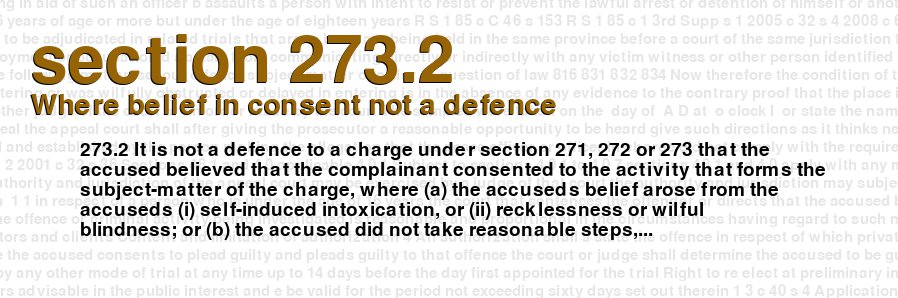

SECTION WORDING

273.2 It is not a defence to a charge under section 271, 272 or 273 that the accused believed that the complainant consented to the activity that forms the subject-matter of the charge, where (a) the accused’s belief arose from the accused’s (i) self-induced intoxication, or (ii) recklessness or wilful blindness; or (b) the accused did not take reasonable steps, in the circumstances known to the accused at the time, to ascertain that the complainant was consenting.

EXPLANATION

Section 273.2 of the Criminal Code of Canada is a provision that is designed to prevent individuals from using their own ignorance or irresponsibility as a defence when it comes to criminal charges relating to sexual assault or other forms of non-consensual activity. The section makes it clear that in cases of sexual assault, it is not a defence for the accused to argue that they believed the complainant had consented to the activity. The provision specifically targets situations where an accused individual's belief in consent arises from self-induced intoxication or their own recklessness or wilful blindness. In other words, if a person becomes intoxicated and proceeds to engage in sexual activity without ensuring that the other person is consenting, they cannot argue that they believed the person was consenting. Similarly, if a person fails to take reasonable steps to ascertain whether the other person is consenting, they cannot argue that they believed the person was consenting based on their own unawareness or inattention. Ultimately, section 273.2 reflects the importance of obtaining consent before engaging in any sexual activity. It places the responsibility on individuals to ensure that they are engaging in consensual behaviour, and removes the possibility of using ignorance or carelessness as an excuse. As a result, it serves to protect individuals from sexual assault and promotes a culture of respect for bodily autonomy and consent.

COMMENTARY

Section 273.2 of the Criminal Code of Canada is an important legal provision that encompasses the issue of consent in the context of sexual offences. This provision stipulates that an individual cannot use their belief that the complainant consented to the activity that forms the subject-matter of the charge as a defence against a charge under section 271, 272, or 273, if that belief arises from self-induced intoxication, recklessness or wilful blindness, or if the accused did not take reasonable steps to ascertain that the complainant was consenting. This commentary aims to discuss the significance of this provision, its application and limitations. One of the primary aims of Section 273.2 is to address the issue of sexual assault and ensure that perpetrators are held accountable for their actions. In many cases of sexual assault, the perpetrator may argue that they believed that the complainant consented to the sexual activity, or that the complainant had given them signals that suggested consent. This defence used to be accepted in courts, which meant that perpetrators could avoid conviction even if the victim did not give their explicit consent. However, this was changed with the introduction of Section 273.2, which provides that the defence of mistaken belief in consent will not apply in certain circumstances. Under Section 273.2, if the accused's belief in consent arose from their own self-induced intoxication, they cannot use it as a defence. This is because the law recognizes that individuals who are intoxicated may not fully comprehend the situation and that their judgement may be impaired. Similarly, the law also recognizes that individuals who are reckless or wilfully blind cannot claim that they believed that the complainant was consenting, as their actions were a result of their own disregard for the situation. Finally, if an accused person did not take reasonable steps to ascertain whether the complainant was consenting, which could have been done in the circumstances known to the accused at the time, this can be used as evidence against them. The importance of this provision is that it makes it clear that consent is critical in cases of sexual offences and that it is the responsibility of the accused person to ensure that they have explicit consent from the other person involved. This is particularly important as sexual assault cases are often challenging to prove as there may not be physical evidence, and the credibility of the complainant may be questioned. To get a successful conviction for sexual offences, prosecutors need to ensure that the accused knew or should have known that the complainant did not consent to the activity before proceeding with it. However, there are limitations to the application of Section 273.2. For instance, the provision only applies to certain sections of the Criminal Code of Canada, including sections 271, 272, and 273, which cover sexual assault, sexual assault with a weapon, and sexual assault causing bodily harm. Thus, there are other sexual offences where this provision does not apply, which may create confusion or inconsistencies in the legal system. Moreover, it may be challenging to determine what constitutes "reasonable steps" in the circumstances at the time of the offence, as this would depend on the facts of each case. In conclusion, Section 273.2 of the Criminal Code of Canada is an essential provision that aims to protect individuals from sexual assault. It recognizes that consent must be explicit and voluntary and that an individual cannot use their belief in consent as a defence if it arose from self-induced intoxication, recklessness or wilful blindness, or if they did not take reasonable steps to ascertain consent. Although it has limitations, this provision is critical in ensuring that perpetrators are held responsible for their actions and that victims' rights are protected.

STRATEGY

Section 273.2 of the Criminal Code of Canada creates a strict liability regime for sexual offences, which means that an accused person cannot rely on an honest but mistaken belief in consent as a defence. This provision applies to offences under section 271 (sexual assault), section 272 (sexual assault with a weapon, threats to a third party, or causing bodily harm), and section 273 (aggravated sexual assault). The provision creates two exceptions to the strict liability regime. First, an accused person may rely on their belief in consent if it was based on the complainant's communicated consent. Second, an accused person may also rely on their belief if they took reasonable steps to ascertain that the complainant was consenting. Strategic considerations when dealing with this section of the Criminal Code will depend on the specific circumstances of each case. However, there are some general strategies that defence counsel may employ. One strategy is to challenge the credibility of the complainant's evidence. Since the Crown does not need to prove lack of consent under section 273.2, it may be more difficult for the Crown to establish the elements of the offence beyond a reasonable doubt if there are inconsistencies or gaps in the complainant's testimony. Another strategy is to establish that the accused took reasonable steps to ascertain that the complainant was consenting. This may involve exploring whether there were any communication or contextual factors that would have led the accused person to believe that the complainant was consenting, such as prior sexual history or non-verbal cues. A third strategy is to argue that the accused did not have the requisite mental state for criminal liability. Specifically, defence counsel may argue that the accused was not reckless or wilfully blind in their belief in consent, or that the accused's self-induced intoxication did not deprive them of the ability to form the necessary mens rea. It is important for defence counsel to carefully review all of the evidence and consider all possible defences and strategies before proceeding with a trial. Ultimately, the success of any defence will depend on the strength of the evidence and the persuasiveness of the legal arguments presented.